It wasn’t really a surprise, but it may well have been a mistake. The FOMC decided to once again leave the Fed Funds rate unchanged at 4.25–4.50%, where it has been since December. But unlike prior hold decisions, this was not a unanimous one; it was anything but. Two governors (Waller and Bowman) dissented in favor of a 25 bp cut—the first time in decades that two governors opposed the majority decision. A recent speech by Governor Waller arguing the case for a cut had signaled his dissent for some weeks. That Governor Bowman joined him makes the move more poignant.

We side with the minority, for reasons we’ve long outlined in these pages and in this opinion piece a month ago. We concede that the case for cuts right now is not overwhelming. If it were, they’d have already been delivered. But the Fed should not wait until the evidence is irrefutable. And while the incoming data remains mixed rather than unmistakably weak, the signs of resilience are less compelling than the evidence of erosion. Policy restrictiveness should be reduced.

Two data releases this week highlight the point. Real GDP grew 3.0% saar in Q2, but this was largely the result of an import plunge that added 5.0 percentage points to growth. Consumer spending grew 1.4% and private fixed investment just 0.4%. The former is uninspiring; the latter is outright weak. On one hand, we don’t want to make too much of trade’s role in Q2 since this was largely a reversal of Q1 (when trade subtracted 4.6 ppt from growth). But at 1.2% saar, final sales to domestic private buyers show a clear deceleration in activity—notably, to below trend—that advises some caution.

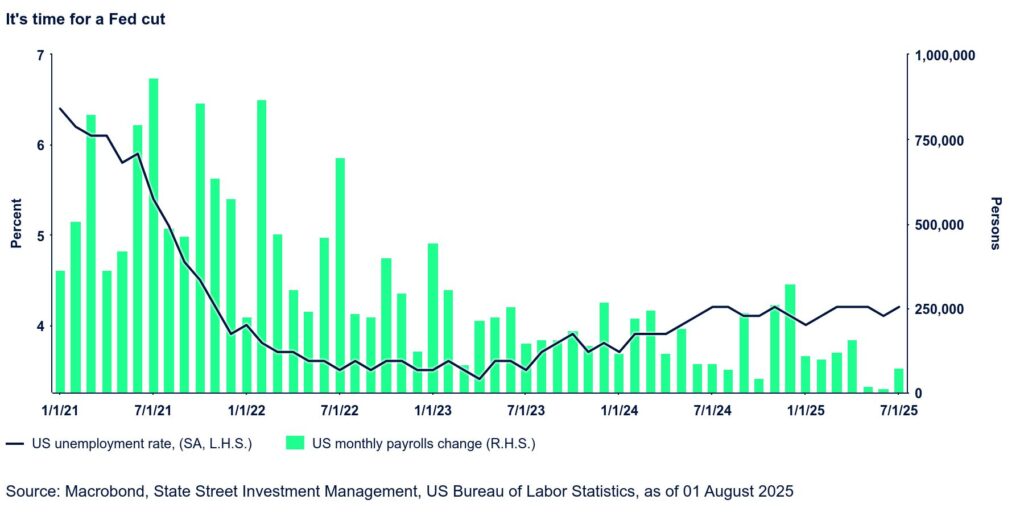

Even more importantly, despite an unemployment rate still at the estimated neutral rate of 4.2% (4.248%), the cumulative evidence points to deteriorating labor market conditions. Even before the July payrolls report changed the labor market picture for the worse, the evidence of weak labor demand had been proliferating. The Conference Board labor differential slipped to its lowest level since March 2021, layoffs have risen, the unemployment duration has lengthened, and hours worked remain stuck at low levels.

Employment itself had remained fairly resilient, but the latest data now put that into question. Non-farm payrolls increased by 73k in July, missing expectations by about 30k. Not great, but not terrible. The true bombshell, however, was the unprecedented (outside of Covid) 258k downward revision to the prior two months. May, initially reported at 144k, is now 19k; June, initially reported at 147k, is now 14k. The magnitude of these revisions is difficult to explain, beyond the fact that the suspicious strength in public education employment reported last month has now been wiped away. It is possible that the revision itself will be partly offset by new data next month, but the message to us remains clear: we are moving away from full employment in the broad definition of the concept.

Having declined to lower interest rates at the July meeting, the FOMC should avail the next opportunity in September—and perhaps even contemplate a 50 bp cut.